Bulletproofing a Billion-Dollar Verdict: In a Case of High Intrigue, DuPont Tries to Defend its Kevlar Trade Secrets Win on Appeal

5 minute read | June.06.2013

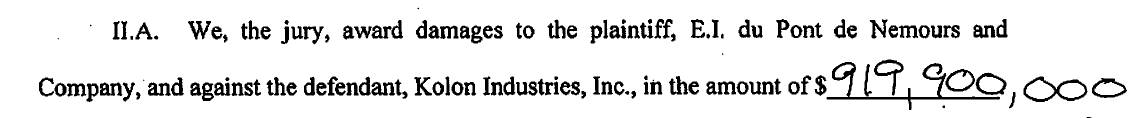

Double agents. Bribery. Top-secret industrial facilities. Code words. An undercover FBI operation, complete with a wire. The DuPont v. Kolon Industries trade secrets trial had all the elements of a spy novel—and it ended with the legal equivalent of a nuclear bomb: a nearly $1 billion jury verdict:

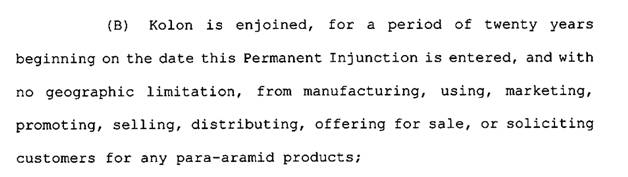

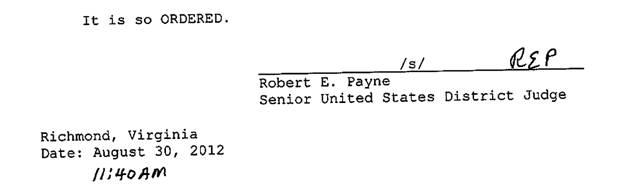

and a worldwide injunction:

These two parties slugged it out at trial, then stepped back into the ring for another battle royale at the Fourth Circuit. As the appeals court considers the arguments, we thought this was a good time to survey this mother of all trade secret cases, and see what’s at stake. Trade Secrets Watch reviewed the ponderous briefs and the trial and appellate arguments, and extracted the juiciest nuggets from this truly salacious saga.

DuPont alleged Kolon stole trade secrets concerning Kevlar, the fiber used in bulletproof armor. When the courtroom shootout ended after the September 2011 trial, the legal wreckage for Kolon was staggering:

- eighteen months in the slammer for David Michael Mitchell, a Kolon consultant and former DuPont employee who pled guilty to stealing DuPont’s trade secret secrets and funneling them to Kolon;

- indictments against Kolon executives for solicitation and misappropriation of DuPont’s trade secrets;

- the mammoth $920 million judgment against Kolon for violating Virginia’s Uniform Trade Secrets Act following a seven-week civil jury trial;

- the worldwide injunction prohibiting Kolon from making, using or selling any para-aramid product for 20 years; and

- a spoliation of evidence order and adverse inference jury instruction against Kolon.

- The district court eviscerated Kolon’s ability to defend itself by a series of one-sided rulings, including granting all of DuPont’s motions in limine and denying all of Kolon’s;

- The district court improperly excluded evidence showing that many of DuPont’s alleged trade secrets weren’t “secret” at all, but that DuPont disclosed them in open court during a prior patent suit against a competitor (Kolon says that many of them are even available in the National Archives);

- The district court improperly allowed DuPont to present its 149 trade secrets en masse, and to continually change what trade secrets it was pursuing at trial;

- DuPont didn’t prove Kolon actually used the secrets and instead tried to establish that Kolon’s mere possession was enough to establish use;

- The district court improperly prejudiced the jury with its sweeping adverse inference instruction based on spoliation of evidence, ignoring that Kolon had issued a document preservation notice and was able to recover most of the documents;

- The district court improperly prejudiced the jury with another adverse inference instruction, telling the jury it could draw adverse inferences against Kolon based on a third party witness’s invocation of the Fifth Amendment 350 times in his deposition (the FBI apparently sought to interview him the day before he was deposed);

- DuPont’s damages theory — that Kolon avoided nearly $1 billion in development costs — was fundamentally flawed because it was based on DuPont’s historical costs over the entire 30 years of its R&D efforts, including costs to develop technology that Kolon never received or that is in the public domain and without proof that Kolon actually realized any cost savings;

- Adding an injunction on top of a nearly $1 billion verdict represents an incredible windfall for DuPont; Kolon shouldn’t be made to pay nearly $1 billion for trade secrets and then be enjoined from using them.

- DuPont more than adequately gave notice of its claims and identified its trade secrets through, among other things, a 60-page interrogatory response;

- DuPont offered ample trial testimony establishing that its secrets weren’t generally known or readily ascertainable, saying its Virginia plant “resembles a top-secret government facility,” with “many guards and barb-wire fences”;

- DuPont presented extensive evidence of Kolon’s alleged “massive theft” of DuPont trade secrets, including evidence that Kolon “bribed former DuPont employees to turn over Kevlar trade secrets; it surreptitiously copied documents and computer files from those ex-employees; it used hidden devices to record meetings; [and] it devised code-words to conceal its discussions,” and DuPont contrasted this evidence with Kolon’s decision not to call a single employee and to rely largely on expert testimony at trial;

- Among the examples DuPont pointed to included an undercover FBI operation in which a DuPont employee posed as a potential consultant and wore a wire to a meeting where a Kolon employee allegedly didn’t want to say what he wanted in writing, out of a concern that it “will create evidence for us … that’s difficult”;

- DuPont also cited evidence that Kolon employees invited Mitchell to a local restaurant, asked him to leave his laptop behind, and surreptitiously copied Kevlar secrets from his laptop while he ate lunch;

- DuPont sought to support the district court’s adverse inference instructions by reference to its extensive fact-finding and 91-page opinion;

- DuPont defended its mega-damages by citing testimony that it cost nearly $1 billion to develop the Kevlar technology, noting that Virgina law permits recovery of the cost savings Kolon would have incurred to develop the trade secrets lawfully on its own, and citing evidence that a plaintiff’s development costs can serve as a fair proxy for the defendant’s avoided costs; and

- It defended the injunction by citing the court’s findings that Kolon allegedly incorporated the misappropriated trade secrets into virtually every stage of the manufacturing process for its competitive product.

Only time will tell if DuPont successfully deflects Kolon’s appellate arguments. Many of Kolon’s arguments appear to turn on discretionary decisions by the trial court that may be difficult to overturn, but we won’t attempt to predict the outcome. We’ll be on the courthouse steps awaiting the court’s decision in the meantime.