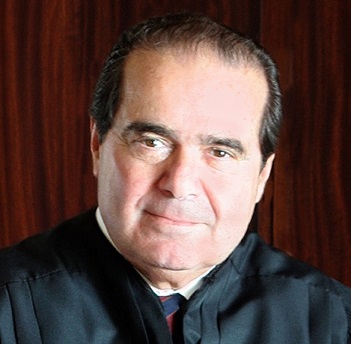

After the passing of Justice Antonin Scalia, we predicted: “Justice Scalia’s passing will immediately impact several employment-related cases pending before the Court.” Specifically, cases in which Scalia was expected to provide the needed fifth vote were at risk of ending in a tie. After two recent rulings from the Court, this prediction appears to have come true.

The noticeable repercussions of a Court composed of an even number of justices were first displayed in Friedrichs v. California Teachers Association et al. When the Court granted certiorari in Friedrichs, some commentators believed the case signaled the death of mandatory union fees for public employees. These commentators’ beliefs were based on their observation that some members of the court, particularly Justice Alito, questioned the Court’s decision in Abood v. Detroit Board of Education upholding mandatory union fees. For instance, the Court’s Harris v. Quinn opinion, which was joined by Scalia, recognized that Abood’s precedential value may be outdated and laid on “questionable foundations.” However, a few observers thought Scalia’s position was in doubt and believed Justice Scalia would serve in the traditional Justice Kennedy swing vote role in Friedrichs. This theory was based upon his expressed concern in Lehnert v. Ferris Faculty Association regarding the free rider problem inherent in allowing non agency-fee bargaining unit members to benefit from unions’ overall duty to represent all workers regardless of whether they paid dues. In the end, though, many observers expected that Justice Scalia would side against mandatory agency fees in Friedrichs and overturn Abood. Instead, the shorthanded Court issued a one-page per curiam opinion providing, “The judgment is affirmed by an equally divided Court.”

The Court also appeared to be deadlocked in the case of Zubik v. Burwell, which involves the Affordable Care Act’s contraception mandate. Instead of taking the route it did in Friedrichs, though, the Court directed the Obama administration and religious nonprofits to seek a potential compromise. Currently, it has ordered both sides to file briefs addressing whether there may be alternative ways contraceptives could be supplied to the religious nonprofits’ employees through a company’s insurance provider while still respecting a religious nonprofits’ ideology. If Scalia was still on the Court, many believe he would have voted in favor of the religious nonprofits.

Scalia’s passing not only left the Court’s conservative bloc without its leading figure, it left the Court limited in its decision-making ability. As Friedrichs and Zubik illustrate, sound law cannot come from a split Court. And until a new justice is confirmed, it appears these unusual results may become the norm.