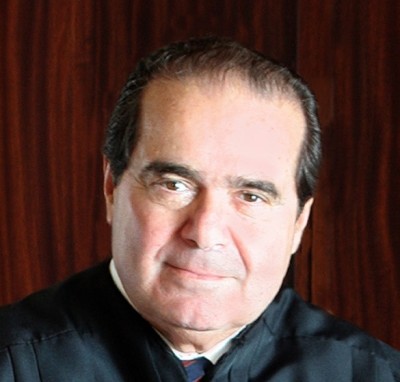

On February 13, 2016, Justice Antonin Scalia, the anchor of the Court’s conservative wing for nearly three decades, passed away. He leaves behind a distinguished legal career that involved experience in wide range of roles. After graduating from Harvard Law School, Justice Scalia entered private practice and then became a law professor at the University of Virginia. He served in the Nixon and Ford administrations, eventually becoming Assistant Attorney General. Scalia then began his judicial ascension when President Ronald Reagan nominated him to the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit. Soon thereafter, Reagan nominated Scalia to the Supreme Court to replace Justice William Rehnquist, whom Reagan had named to the Chief Justice position. Scalia was unanimously confirmed.

No matter what one’s politics, one must acknowledge Scalia’s indelible impact on the Court. His pithy dissents were often scathing indictments, and his theories on originalism and textualism may be two of the most important legal ideologies of our era. And while Justice Scalia may be best remembered for his insights on federalism, abortion, and affirmative action, labor and employment practitioners will continue to borrow from his employment-related jurisprudence for years to come.

Justice Scalia’s 5–4 opinion in Wal-Mart v. Dukes clarified Rule 23’s “commonality” requirement for class action certification and instructed courts to perform a “rigorous analysis” of the plaintiffs’ compliance with the Rule. Similarly, his 5–4 opinion in AT&T Mobility v. Concepcion interpreting the Federal Arbitration Act limited the states’ abilities to create rules prohibiting class action waivers, and paved the way for employers to insert class action waivers into their arbitration agreements as a common practice. He left an impact on discrimination law as well: in Oncale v. Sundowner Offshore Services, Inc. for instance, Justice Scalia wrote for a unanimous Court in concluding that Title VII’s protections on the basis of sex applied equally to same-sex harassment.

Unless the Court tables its cases until a new justice is confirmed, Justice Scalia’s passing will immediately impact several employment-related cases pending before the Court. One such case is Friedrichs v. California Teachers Association et al. from the Ninth Circuit, which observers had predicted the Court would vote to reverse by a 5–4 margin to find that mandatory union fees for public employees are unconstitutional. With Justice Scalia’s absence, the case may result in a 4–4 tie, in which case the Ninth Circuit’s ruling in favor of the union would stand. Likewise, Justice Scalia’s absence may disrupt the outcome in Tyson Food Inc. v. Bouapheko et. al., in which the Court will decide whether the Eighth Circuit’s ruling upholding certification of a class of employees who worked vastly different hours was erroneous and whether it will overturn or limit the Mt. Clemons representative testimony doctrine.

With Justice Scalia’s passing, the Court lost a commanding and influential voice on a wide range of issues; employment law was no exception. Only time will tell how the post-Scalia Court will interpret or modify the legacy he left.