This Memorial Day weekend, we would like to stop and honor the sacrifice that American servicemen and women have made, and take a brief look at an early case involving the military and trade secrets.

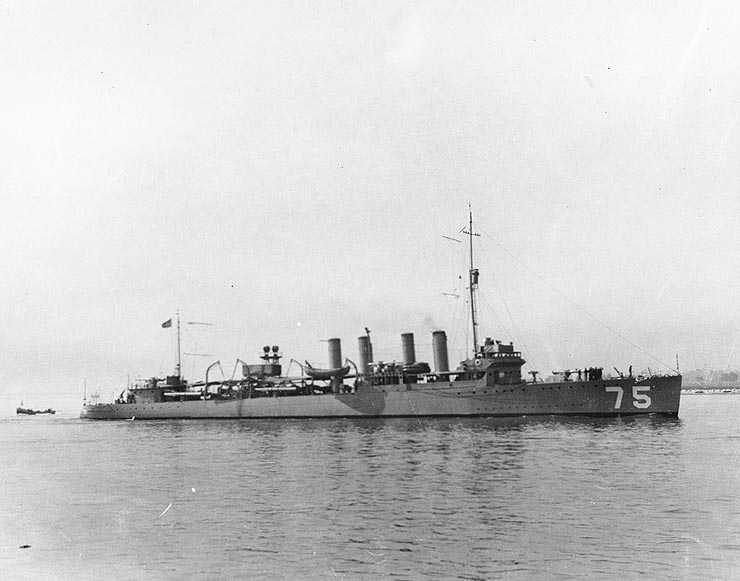

In 1910, the Third Circuit Court of Appeals issued a decision involving a contract with the United States Navy and a dispute over the disclosure of documents related to the construction of destroyers. At the time of this decision, European powers had begun an arms race that would later escalate, and geopolitics were causing tensions that would lead to the First World War.

In re Grove, 180 Fed. 62 (3rd Cir. 1910) originated as a patent case, and a dispute arose as to whether Henry Grove, president of the defendant shipbuilding company, was in contempt for refusing to produce copies of plans and specifications for the Navy destroyers. Grove had refused to produce the documents on the advice of counsel, on the grounds that disclosure would harm the public interest by disclosing military secrets, and would result in the unnecessary disclosure of trade secrets. The Navy’s advertisement for bids had contained numerous requests that information related to bids be kept confidential. The Secretary of the Navy had also stated that disclosure of the documents “would be detrimental to the interests of the United States.”

The federal trial court found Grove in contempt for refusing to turn over the documents. The Third Circuit reversed, concluding that it was reasonable for Grove to decline to produce the documents in the absence of a court order given the statements from the Navy secretary. While this case focused primarily on military secrets, the Third Circuit also revealed an early skepticism of trade secrets:

“In an epoch when patent rights and copyrights for invention are so easily [obtained] and so amply secured, there can be only an occasional need for the preservation of an honest trade secret without resort to public registration for its protection. Such instances do occur, but an object of the patent and copyright laws is to render them as rare as possible, and the presumption should be against their propriety.” (Citing 3 Wigmore on Evidence, § 2212).

Fast-forward a century and there is a far broader recognition of the validity of trade secrets. This can be seen in the fact that nearly every state in the country has adopted the Uniform Trade Secrets Act and in recent promises from the White House to beef up trade secrets protection in an age of global competition and cyber attacks. And while trade secret protection is obviously a critical component of a vibrant economy, that economy ultimately rests on a free society. That free society has always come at a price to someone.

Today, we would like to simply say thank you to those who have paid that price.