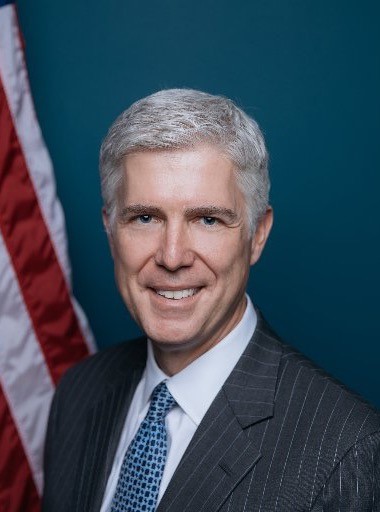

After the Supreme Court sat with an empty seat for more than one year, and following a hard-fought nominations process which saw the failed nomination of Judge Merrick Garland and Republican lawmakers resorting to the “nuclear option,” the Senate confirmed Neil Gorsuch of the Tenth Circuit to be the next Supreme Court Justice. His first day on the job was Monday, April 17th. But for those who are not familiar with Judge Gorsuch, the question remains: what kind of Justice will he be?

Although Supreme Court Justices can—and sometimes famously do—change their judicial philosophies once they’ve joined the Court, commentators often look to a candidate’s judicial record as a way to divine how he or she may rule in future cases. During Justice Gorsuch’s eleven year tenure on the Tenth Circuit, he penned 212 opinions and numerous dissents, ultimately emerging as a strict adherent to the principles of textualism and originalism. In many cases, his judicial tendencies were displayed in his employment law decisions.

Gorsuch has shown reluctance in applying Chevron deference to agency action. In TransAm Trucking v. Administrative Review Board, 833 F.3d 1206 (10th Cir. 2016), dissented from the majority’s ruling that a company violated the whistleblower provisions of the Surface Transportation Assistance Act (“STAA”) when it fired an employee who abandoned cargo after being pressured to work in unsafe conditions. In his dissent, Gorsuch criticized the majority for applying Chevron deference to a loose DOL interpretation of the STAA, especially considering the agency never argued Chevron deference applied to its interpretation. Gorsuch’s seeming disinclination to defer to agency interpretation could prove determinative if the Supreme Court decides whether the anti-retaliation provisions in the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act also apply to whistleblowers who claim retaliation after reporting internally, or whether those protections only apply once an individual reports directly to the SEC. Currently, the Second and Ninth Circuits have given deference to the SEC’s position that internal reporting is protected, while the Fifth Circuit has rejected the position.

In the discrimination context, Gorsuch issued several rulings in cases that were matters of first impression before the Tenth Circuit. In particular, he concluded in Almond v. Unified School Dist. No. 501, 665 F.3d 1174, 1175 (10th Cir. 2011) that the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act only applies to discrimination in compensation claims, not in cases “alleging discrimination in hiring, firing, demotions, transfers, or the like.” He also wrote the Tenth Circuit’s opinion concluding that plaintiffs may not maintain an employment discrimination action under Title II of the ADA. See Elwell v. Okla. ex rel. Bd. of Regents of the Univ. of Okla., 693 F.3d 1303, 1305 (10th Cir. 2012). During his tenure on the Tenth Circuit, Gorsuch has shown an open disdain for the McDonnell Douglas burden-shifting framework. For instance, in Paup v. Gear Prods., 327 Fed. Appx. 100 (10th Cir. 2009) he accused the framework of “improperly diverting attention away from the real question posed by the ADEA — whether age discrimination actually took place — and substituting in its stead a proxy that only imperfectly tracks that inquiry.” Most recently in Walton v. Powell, Gorsuch opined, “in the narrow remaining class of (summary judgment, circumstantial-proof) cases, it may be that McDonnell Douglas is properly used only when the plaintiff alleges a ‘single’ unlawful motive — and not ‘mixed motives’ — lurking behind an adverse employment decision. A potentially crippling limitation given that Title VII’s statutory language doesn’t ever require plaintiffs to establish more than mixed motives to prevail. Indeed, given so many complications and qualifications like these, more than a few keen legal minds have questioned whether the McDonnell Douglas game is worth the candle even in the Title VII context.” Although Gorsuch has not discussed how he would modify the McDonnell Douglas test, in his new role as Supreme Court justice, he might seek an opportunity to craft an alternative burden structure for discrimination claims.

Further, Gorsuch has shown a willingness to indulge trade secret holders a full range of remedies to enforce their rights. In one case interpreting the Utah Uniform Trade Secrets Act, Gorsuch rejected the notion a company needs to show an employee derived a commercial gain through misappropriated trade secrets in order to state a claim; instead, disclosure to a competitor was enough to show trade secrets theft regardless of the former employee’s motives. See StorageCraft Technology Corp. v. Kirby, 744 F.3d 1183 (10th Circuit 2014). In another Gorsuch opinion, he rejected the notion that trade secrets could be preempted by patent law, stating, “traditional trade secret claims can peacefully coexist with patent law.” Russo v. Ballard Medical Products, 550 F.3d 1004 (10th Circuit 2008). While these cases fell under state trade secret laws, it remains to be seen whether Gorsuch would look to apply similar analysis to claims involving the federal Defend Trade Secrets Act (“DTSA”). Indeed, the Supreme Court has not heard a case yet involving the DTSA, but issues have been percolating in the lower courts since the DTSA’s enactment.

Finally, Gorsuch’s prior opinions indicate he will likely continue the Supreme Court’s trend finding in favor of pre-emption under the Federal Arbitration Act (“FAA”). In one opinion reversing and remanding a trial court’s decision denying a defendant’s motion to compel arbitration, Gorsuch wrote, “Everyone knows the Federal Arbitration Act favors arbitrations . . . Parties should not have to endure years of waiting and exhaust legions of photocopiers in discovery and motions practice merely to learn where their dispute will be heard. The Act requires courts process the venue question quickly so the parties can get on with the merits of their dispute in the right forum.” See Howard v. Ferrellgas Partners LLP, 748 F.3d 975 (10th Cir. 2014). Similarly, Gorsuch dissented in Ragab v. Howard, 841 F.3d 1134 (10th Cir. 2016), where the majority of the three-judge panel upheld a district court’s denial of a motion to compel arbitration after it determined conflicting arbitration provisions in multiple agreements showed no meeting of the minds between the parties. Gorsuch would have compelled arbitration, explaining “the federal policy favoring arbitration embodied in the FAA and armed with preemptive force” trumped a New Jersey doctrine that prohibited arbitration when multiple contracts contained conflicting terms. Gorsuch may have an opportunity to directly apply this reasoning soon, especially considering the Supreme Court has agreed to hear several consolidated cases concerning the legality of class action waivers in arbitration clauses.

In February of last year, we noted, “With Justice Scalia’s passing, the Court lost a commanding and influential voice on a wide range of issues; employment law was no exception. Only time will tell how the post-Scalia Court will interpret or modify the legacy he left.” Assuming Justice Gorsuch retains his judicial approach, it will re-create the 5-4 majority for the Court’s conservative wing and put an end to many of the 4-4 deadlocks that have occurred since Justice Scalia’s passing. If that is the case, it appears that Scalia’s legacy will remain intact for years to come as Justice Gorsuch fills his vacancy on the Court.