On October 13, 2016, the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (the “CFTC”) approved an Order delaying for one year the reduction of the threshold for determining whether an entity constitutes a “swap dealer” for purposes of the U.S. Commodity Exchange Act.[1] Currently, persons are not considered to be swap dealers unless their swap dealing activity in aggregate gross notional amount measured over the prior 12-month period exceeds a de minimis threshold of $8 billion. This threshold had been scheduled to automatically decline to $3 billion on December 31, 2017, but the Order extended that date to December 31, 2018, absent further action from the CFTC.

The delay in the threshold decline follows the recent issuance by the CFTC of the Swap Dealer De Minimis Exception Final Staff Report (the “Final Report”).[2] The Final Report supplemented a preliminary report (the “Preliminary Report”)[3] on the same matters and provided a summary of numerous comment letters the CFTC received in response to that report, as well as further data analysis. These two reports together comprise the “report” contemplated by CFTC Regulation 1.3(ggg)(4)(ii)(B), which directed the CFTC to issue a report on topics relating to the definition of the term “swap dealer” and the de minimis threshold.

The Preliminary Report analyzed available swap data (primarily from the four swap data repositories (“SDRs”) registered with the CFTC) during the period from April 1, 2014, through March 31, 2015, for five asset classes: interest rate swaps (“IRS”), credit default swaps (“CDS”), non-financial commodities (“Non-Financial Commodities”), foreign exchange derivatives and equity swaps. However, the CFTC noted in the Final Report that it faced numerous challenges in data quality available from the SDRs, including a lack of information regarding whether a swap was entered into for dealing purposes and a lack of reliable notional data for all but IRS and CDS.[4]

The CFTC solicited comments on several topics in the Preliminary Report, including: (i) whether the current de minimis threshold should be maintained, raised or reduced; (ii) whether swaps that are executed on a swap execution facility (“SEF”) or designated contract market (“DCM”) and/or centrally cleared should be excluded from an entity’s de minimis calculation; (iii) whether the de minimis exception should be based on multiple factors (e.g., number of counterparties) instead of only gross notional swap dealing activity; (iv) whether a de minimis threshold should be established for each asset class; and (v) whether the current exclusion available to insured depositary institutions should be expanded. The CFTC received 24 comment letters from banks, industry groups, legislators and other market participants and interested parties in response to the Preliminary Report.

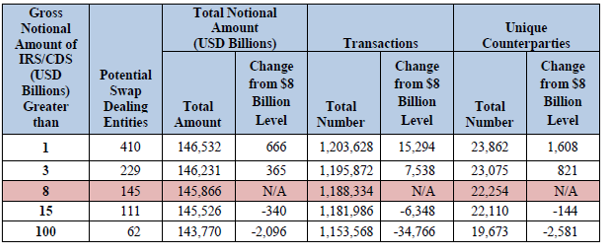

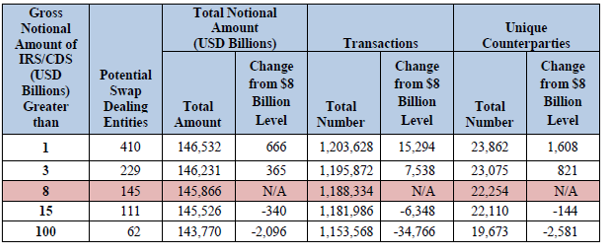

The Final Report analyzed an additional one-year period of data for the IRS, CDS and Non-Financial Commodity asset classes to the period considered in the Preliminary Report.[5] The primary conclusion of the Final Report was that “only a substantial increase or decrease in the de minimis threshold would have a significant impact on the amount of IRS and CDS covered by swap dealer regulation, as measured by notional amount, transactions, or unique counterparties.”[6] The following chart from the Final Report summarized the results leading to this conclusion:[7]

Table 1 – IRS and CDS Potential Dealing Activity Covered by Notional Amount

Consistent with the Preliminary Report, the Final Report estimated that approximately 84 additional entities (from 145 to 229 entities) trading IRS and CDS might have to register as swap dealers if the de minimis threshold declined to $3 billion. However, this 58% increase in the number of entities regulated would result in coverage of less than 1% of additional notional activity and swap transactions, and only 4% of additional unique counterparties. Interestingly, as reflected in the table set forth above, an increase of the de minimis threshold to $15 billion would yield similar results: 34 fewer entities having to register, but reduced coverage of less than 1% of additional notional activity, swap activity and unique counterparties.

Moreover, the data analyzed indicated that a substantial majority of swaps (99% of IRS, 99% CDS and 89% Non-Financial Commodity swaps) involved a registered swap dealer during the final review period. In conclusion, the CFTC stated that it may want to consider whether to set the de minimis threshold to its current $8 billion threshold, allow the threshold to decline to $3 billion, as scheduled, or delay the reduction of the threshold while it continues its efforts to improve data quality.

Separately, the Final Report indicated that the comments received generally expressed support for excluding from an entity’s de minimis calculations swaps entered into on a SEF or DCM and/or centrally cleared, but that the CFTC had not had sufficient time to evaluate several factors that could impact the implementation of such an exclusion.[8]

In addition, the Final Report stated that the CFTC may want to consider: (i) maintaining a single de minimis threshold based on notional amount (instead of a threshold based on multiple factors); and (ii) maintaining the single gross notional de minimis exception (instead of adopting a class-specific approach) or consider adopting a class-specific approach in the future as data quality improves.[9]

Finally, the Final Report indicated that the CFTC may want to consider whether the conditions to the current exclusion to the swap dealer definition for insured depository institutions are overly-restrictive.

[1] Order Establishing De Minimis Threshold Phase – In Termination Date, 81 Fed. Reg. 71, 605 (October 18, 2016).

[2] Swap Dealer De Minimis Exception Final Report, August 15, 2016 (available at http://www.cftc.gov/idc/groups/public/@swaps/documents/file/dfreport_sddeminis081516.pdf).

[3] Swap Dealer De Minimis Exception Preliminary Report, November 18, 2015 (available at: http://www.cftc.gov/idc/groups/public/@swaps/documents/file/dfreport_sddeminis_1115.pdf). For a summary of this report, click here.

[4] Final Report, at 5.

[5] The CFTC focused on IRS and CDS data because reliable notional data was not available for the other asset classes. Final Report, at 20. The Final Report highlighted that many of the same limitations noted in the Preliminary Report for Non-Financial Commodity swaps persisted, but that the CFTC nevertheless performed an analysis using counterparty and transaction counts for this asset class. Id. at 19-20.

[6] Id. at 20.

[7] Id. at 21 (Table 1).

[8] Id. at 25.

[9] Id. at 26.